Издателство |

| :. Издателство

LiterNet |

Медии |

| :. Електронно списание LiterNet |

| :. Електронно списание БЕЛ |

| :. Културни

новини |

Каталози |

| :. По

дати : Март |

| :. Електронни книги |

| :. Раздели / Рубрики |

| :. Автори |

| :. Критика за авторите |

Книжарници |

| :. Книжен

пазар |

| :. Книгосвят: сравни цени |

Ресурси |

| :. Каталог за култура |

| :. Артзона |

| :. Писмена реч |

За

нас |

| :. Всичко за LiterNet |

CULTURAL MONUMENTS OF THE NATIONAL REVIVAL PERIOD

Margarita Koeva

web | Архитектурното наследство...

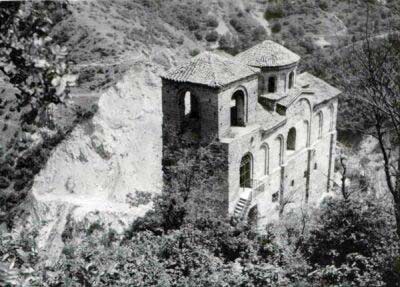

Ecclesiastical architecture formed a major part of that art in the centuries of Ottoman rule and the period of the Bulgarian National Revival. Its development can nerve as a record of the artistic phenomena characteristic or this epoch.

The

years between the 17th and 18th centuries saw the beginning of economic processes

which changed the social structure of the Balkan peoples and laid the foundations

of their National and Cultural Revival. These processes were considerably hampered

in the Bulgarian lands by the proximity of these lands to the centre of the

Ottoman Empire, and by the fact that the roads connecting Europe and Asia, of

vital importance to the Eastern and the western world, passed through them.

This complicated the political situation in which the Bulgarian nation was being

formed and rendered still harder the conditions in which the Bulgarians were

moving from the stagnant mediaeval fonts of economic and cultural lire officially

imposed upon them to the economics and culture of the bourgeois world.

The

years between the 17th and 18th centuries saw the beginning of economic processes

which changed the social structure of the Balkan peoples and laid the foundations

of their National and Cultural Revival. These processes were considerably hampered

in the Bulgarian lands by the proximity of these lands to the centre of the

Ottoman Empire, and by the fact that the roads connecting Europe and Asia, of

vital importance to the Eastern and the western world, passed through them.

This complicated the political situation in which the Bulgarian nation was being

formed and rendered still harder the conditions in which the Bulgarians were

moving from the stagnant mediaeval fonts of economic and cultural lire officially

imposed upon them to the economics and culture of the bourgeois world.

Within the historical framework architectural development also bore the marks of this unnatural situation. Although in the most general lines, it unambiguously possessed the character of an architectural Renaissance, it also had certain specific features which distinguished it from the Renaissance in Europe.

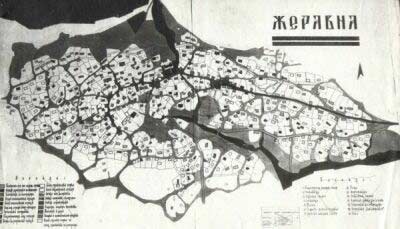

Bulgarian

National Revival architecture, like any Renaissance architecture, was the child

of the urban culture of that epoch. In contrast to the European urban culture,

which appeared in the large cities, it came into being in our country in the

small craft and trade towns inhabited by Bulgarians, far from the great roads

and preserved from Turkish attacks and colonization. Although these towns were

not large, the manner of production, the social structure and culture in them

were urban in type. An art and architecture, which were new in character, came

into being here, and the Bulgarian Renaissance developed. Its features were

first manifested in ecclesiastical architecture. If this fact is to be correctly

understood, the historical conditions existing in the centuries of Ottoman bondage

should again be referred to. In the period of bondage the only public construction

officially permitted to the Bulgarians was hat of churches. The Bulgarian population

was deprived of an independent public life, and in the course of almost five

centuries - from the mid-15th to the mid-19th century - the churches and monasteries

replaced all the other kinds of public buildings. That is way ecclesiastical

architecture acquired the traits of civic architecture, becoming pliable, rapidly

changing its typology and compositional system, and reacting to the changes

in the political and social scene. From the l8th century onwards traits of new

architectural and artistic principles and qualitative changes manifested themselves.

It was in ecclesiastical architecture that the initial transition from the mediaeval

architectural system to that of the new age was realized.

Bulgarian

National Revival architecture, like any Renaissance architecture, was the child

of the urban culture of that epoch. In contrast to the European urban culture,

which appeared in the large cities, it came into being in our country in the

small craft and trade towns inhabited by Bulgarians, far from the great roads

and preserved from Turkish attacks and colonization. Although these towns were

not large, the manner of production, the social structure and culture in them

were urban in type. An art and architecture, which were new in character, came

into being here, and the Bulgarian Renaissance developed. Its features were

first manifested in ecclesiastical architecture. If this fact is to be correctly

understood, the historical conditions existing in the centuries of Ottoman bondage

should again be referred to. In the period of bondage the only public construction

officially permitted to the Bulgarians was hat of churches. The Bulgarian population

was deprived of an independent public life, and in the course of almost five

centuries - from the mid-15th to the mid-19th century - the churches and monasteries

replaced all the other kinds of public buildings. That is way ecclesiastical

architecture acquired the traits of civic architecture, becoming pliable, rapidly

changing its typology and compositional system, and reacting to the changes

in the political and social scene. From the l8th century onwards traits of new

architectural and artistic principles and qualitative changes manifested themselves.

It was in ecclesiastical architecture that the initial transition from the mediaeval

architectural system to that of the new age was realized.

The

European Renaissance created a new architectural system by rejecting the Gothic

sttyle. Cur National Revival was slower, far more closely linked with tradition,

but in the final count it also rejected the Middle Ages in order to create the

New Bulgarian architecture. It is one of the specific features of this architecture

that the rejection of mediaeval cultural standards in art was connected with

the struggle against the officially imposed Ottoman culture, in essence inert

and mediaeval. In. this way the cultural processes acquired a clearly marked

political trend and the character of a struggle for national self-determination.

The

European Renaissance created a new architectural system by rejecting the Gothic

sttyle. Cur National Revival was slower, far more closely linked with tradition,

but in the final count it also rejected the Middle Ages in order to create the

New Bulgarian architecture. It is one of the specific features of this architecture

that the rejection of mediaeval cultural standards in art was connected with

the struggle against the officially imposed Ottoman culture, in essence inert

and mediaeval. In. this way the cultural processes acquired a clearly marked

political trend and the character of a struggle for national self-determination.

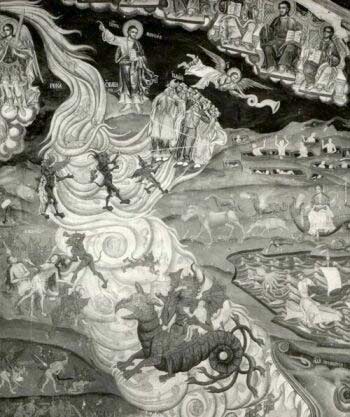

At the same time traditional thinking made way for the new humanistic world outlook and the new aesthetics. Ecclesiastical architecture and art, despite their traditional character, were unable to remain unaffected by this process. The church buildings of the National Revival period bear the imprint of a civic ideology in which the theological thinking of the Middle Ages participated only as an artistic and symbolical system, having long since lost its real sense. Ecclesiastical art introduced a new content into the traditional iconographic types, acquiring a civic and didactic character; gradually but inevitably detached from the great art. Of the Bulgarian Middle Ages, It was to make way for the new secular art of the National Revival. The builders of this period gave up the mysticism of mediaeval architecture. They drove out the supernatural from the church buildings and turned them into halls flooded with light. Imparting a new content which was not always suitable in character. However, this revolutionary process was simultaneously and intricately interwoven with tradition. In order to explain this fact it is necessary to elucidate the painful road along which Bulgarian culture in the sphere of the arts passed after the destruction of its official foundations at the fall of the Second Bulgarian Kingdom.

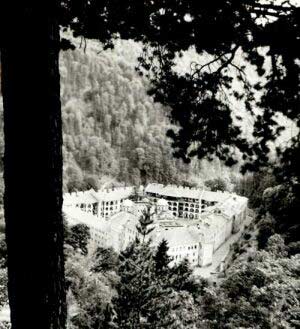

It

felt to the lot of ecclesiastical architecture and art to carry over down the

centuries of political arid cultural bondage the traditions of mediaeval Bulgarian

culture and construction. Having lost its independence at a time when it was

on the threshold of the transition to new phenomena, under the conditions of

bondage this culture passed over to a ‘second’, unofficial level and became

a popular, folk culture. Ecclesiastical art and architecture ceased to express

a state ideology and became the possession of the raya (non-Moslem population),

the enslaved Bulgarians, deprived of access to the official culture. The adoption

of many elements of folk culture in religious art followed as a natural consequence.

Gradually the mediaeval archtypes acquired folk traits. Although the general

schemata hallowed by tradition, were preserved, the types of church buildings

manifested a number of elements from folk construction. Their external architecture

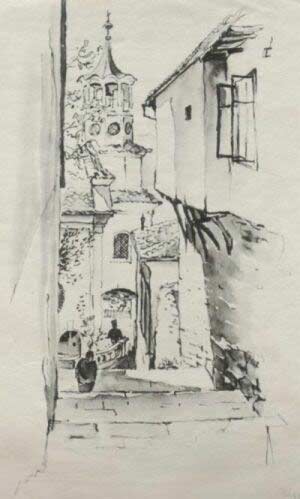

changed particularly rapidly. The churches hid among the house in the towns

and villages and their outward appearance did not betray their function. Only

their interior preserved the traditional forms and elements, and sometimes exceptional

works of art and the art crafts were created in them.

It

felt to the lot of ecclesiastical architecture and art to carry over down the

centuries of political arid cultural bondage the traditions of mediaeval Bulgarian

culture and construction. Having lost its independence at a time when it was

on the threshold of the transition to new phenomena, under the conditions of

bondage this culture passed over to a ‘second’, unofficial level and became

a popular, folk culture. Ecclesiastical art and architecture ceased to express

a state ideology and became the possession of the raya (non-Moslem population),

the enslaved Bulgarians, deprived of access to the official culture. The adoption

of many elements of folk culture in religious art followed as a natural consequence.

Gradually the mediaeval archtypes acquired folk traits. Although the general

schemata hallowed by tradition, were preserved, the types of church buildings

manifested a number of elements from folk construction. Their external architecture

changed particularly rapidly. The churches hid among the house in the towns

and villages and their outward appearance did not betray their function. Only

their interior preserved the traditional forms and elements, and sometimes exceptional

works of art and the art crafts were created in them.

In

the 15th and 16th centuries the single-nave without a dome became the basic

type of church buildings a type which had formerly existed for the people or

as a small family chapel. At that time, under the conditions of bondage, it

was the only type which could be built, despite bans and restrictions, and most

often by digging it entirely or partly into the ground. The inner space of these

single-nave churches was small, they were roofed with semibarrel vaults, their

windows were also small, while their inside walls were entirely covered with

mural paintings. The mural ornamentation preserved the artistic traditions of

the mediaeval schools and often snowed high professional standards.

In

the 15th and 16th centuries the single-nave without a dome became the basic

type of church buildings a type which had formerly existed for the people or

as a small family chapel. At that time, under the conditions of bondage, it

was the only type which could be built, despite bans and restrictions, and most

often by digging it entirely or partly into the ground. The inner space of these

single-nave churches was small, they were roofed with semibarrel vaults, their

windows were also small, while their inside walls were entirely covered with

mural paintings. The mural ornamentation preserved the artistic traditions of

the mediaeval schools and often snowed high professional standards.

The 17th century brought certain changes in the development of ecclesiastical art and architecture. The churces increased in size. They became wider and more spacious, their interiors grew larger and this imposed new systems of construction. Doubling arches were built under the vaults, and niches, pilasters and semi-columns appeared on the inside walls. These structural elements led to changes in the development of both architecture and the mural decoration. They foretold the procesees of renovation which the ecclesiastical architecture of the National Revival period was later to undergo. In this sense the single-nave churches of the 15th and 16th centuries are a genetic step in the National Revival development, while the l7th century may rightly be called Pre-National Revival’. The new elements in architecture and art, connected with the vital sources of folk art, paved the way for the humanistic art of the National Revival.

The

church occupied a special place in the general ideology of the National Revival

period. Eaving lost her ecclesiastical and administrative independence after

the Bulgarian kingdom had fallen under Ottoman bondage, the Bulgarian church

did not possess the right to represent the Bulgarian nationality within tile

frontiers of the Empire, a right which the Patriarchate or Constantinople had

tacitly acquired as early as the 15th century. The Greek clergy availed

itself of this circumstance to implement the idea of a spiritual assimilation

it had held for long. The struggle for an autonomous Bulgarian church was actually

a struggle for the the Bulgarian nationality and essentially a political struggle.

This gave ecclesiastical construction the character of public architecture with

a civic purpose. According to the customary law, tacitly accepted in the Ottoman

Empire, every temple, regardless of the religion to which it belonged, was inviolable

and could not be attacked. These customs, observed to a great extent in times

of peace, made independent Bulgarian territory of the church buildings, monasteries

and church courtyards. All the social manifestations of tile Bulgarian population

were concentrated around church and monastery. Ecclesiastical architecture thus

acquired the functions of Bulgarian civic architecture. These functions gradually

took on an increasingly large role, and parallel with the dying mediaeval world

outlook changed the character of ecclesiastical construction. The ecclesiastical

architecture of the National Revival period played a responsible civic and patriotic

part. It expressed the growing national self-confidence, and served as a centre

for the processes of national self-determination of which religion was the outer

form imposed by circumstances.

The

church occupied a special place in the general ideology of the National Revival

period. Eaving lost her ecclesiastical and administrative independence after

the Bulgarian kingdom had fallen under Ottoman bondage, the Bulgarian church

did not possess the right to represent the Bulgarian nationality within tile

frontiers of the Empire, a right which the Patriarchate or Constantinople had

tacitly acquired as early as the 15th century. The Greek clergy availed

itself of this circumstance to implement the idea of a spiritual assimilation

it had held for long. The struggle for an autonomous Bulgarian church was actually

a struggle for the the Bulgarian nationality and essentially a political struggle.

This gave ecclesiastical construction the character of public architecture with

a civic purpose. According to the customary law, tacitly accepted in the Ottoman

Empire, every temple, regardless of the religion to which it belonged, was inviolable

and could not be attacked. These customs, observed to a great extent in times

of peace, made independent Bulgarian territory of the church buildings, monasteries

and church courtyards. All the social manifestations of tile Bulgarian population

were concentrated around church and monastery. Ecclesiastical architecture thus

acquired the functions of Bulgarian civic architecture. These functions gradually

took on an increasingly large role, and parallel with the dying mediaeval world

outlook changed the character of ecclesiastical construction. The ecclesiastical

architecture of the National Revival period played a responsible civic and patriotic

part. It expressed the growing national self-confidence, and served as a centre

for the processes of national self-determination of which religion was the outer

form imposed by circumstances.

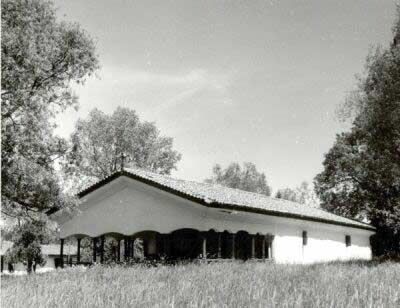

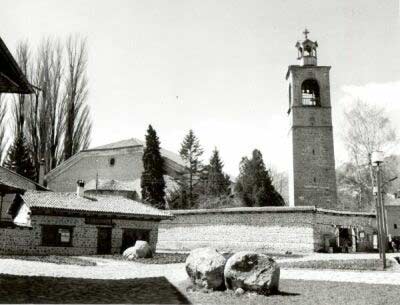

The

most suitable form for church buildings fulfilling such civic functions was

the basilica type of church with a nave and two aisles. Wide, spacious and ensuring

the sane conditions for all who attended the services, it was best suited to

the democratic spirit of the time and to its humanistic ideals. Appearing in

the early years of the 18th century this type of church spread rapidly to all

regions in the Bulgarian lands. From the middle of the century the building

of new churches proceeded at a very fast rate, particularly after the troubled

times of the Kurdjaii disorders in the second decad of the 19th century. Almost

no Bulgarian town or village was then left in which a new church was not built.

In the large towns every quarter had its own church. The churches grew larger,

higher and occupied a prominent place in the towns and villages. School buildings

were erected in their courtyards, there were rooms for the sittings of the craft

guilds, the church and schoolboards, etc. Their courtyards became the centres

of cultural life in town and village.

The

most suitable form for church buildings fulfilling such civic functions was

the basilica type of church with a nave and two aisles. Wide, spacious and ensuring

the sane conditions for all who attended the services, it was best suited to

the democratic spirit of the time and to its humanistic ideals. Appearing in

the early years of the 18th century this type of church spread rapidly to all

regions in the Bulgarian lands. From the middle of the century the building

of new churches proceeded at a very fast rate, particularly after the troubled

times of the Kurdjaii disorders in the second decad of the 19th century. Almost

no Bulgarian town or village was then left in which a new church was not built.

In the large towns every quarter had its own church. The churches grew larger,

higher and occupied a prominent place in the towns and villages. School buildings

were erected in their courtyards, there were rooms for the sittings of the craft

guilds, the church and schoolboards, etc. Their courtyards became the centres

of cultural life in town and village.

The development ecclesiastical construction in the period of the national Revival passed through three main stages. A definite type of church building is characteristic of each of these stages, and the development of this type within, the limits of the given period has its own specifics. The limits of these stages are determined by several great historical events. They coincided with the basic subdivisions of the National Revival period.

The first stage began about the Middle of the 18th century and covered the time up to end of that century when the Kurdjali disorder began. The appearance of the first churches of the type with a nave and two aisles determines the beginning of the new age in Bulgarian architectural development. They were the result of the new economic processes of the Bulgarian population’s growing prosperity and independence, and of the striving to express national consciousness through the self-determination of the church. The large churches of this type, which are like the Italian Renaissance basilicas, have saddle roofs and at least at first sight do not stand, out in the general silhouette of the town or village in which they were built.

The first of them were built in towns where this type of church had been known in the Middle Ages and where old churches of this kind had been preserved. They were towns or villages economically sound, enjoying comparative independence and good connections with the outside world. Sufficient information as to what was going on outside the boundaries of the Empire reached them by way of trade. The influences of foreign culture in constructions art reached them in the same way and found favourable soil in their economic prosperity. Churches with a single nave and two aisles were built for the first time in Melnik, Sozopol, Assenovgrad, Samokov, Rousse and Pleven. They had spacious interiors and their architecture was extremely simplified on the exterior. The individual parts of their compositional plan were: the nave, the apse, a spacious narthex to which an arched outer gallery was sometimes added instead of the exonarthex of the Early Christian basilicas. These traditional divisions of the churches were preserved unchanged in number and kind during the entire period of tile National Revival. Changes only set in the form and size of each of them.

The most important examples of church architecture in the initial stage of development in the National Revival period are the churches of: St Nicholas in Melnik (1756); the Holy Virgin in. Sozopol built on to the apse of an old church, probably of the 16th century, in 1781; Holy Trinity Church in Rousse, a majestic building of a nave and two aisles built in 1764, and the Metropolitan Church in Samokov (1795-1805). The fact that they were all built in regions in which the mediaeval tradition was still alive, in the place of older churches, parts of which remained built into the new church is a distinctive feature of them. all. The tradition was thus not only accepted, but continued in the most literal sense - the old construction was woven into the new, and naturally transmitted some of’ its features to it.

In

the treatment of the inner space the churches with a nave and two aisles differed

totally from the single-nave churches. The nave of the former is not simply

a triple repetition of the single nave of the letter. It offers a qualitatively

new spatial, compositional and plastic problem. It is precisely in the nave

that the features of the new architectural system are the most clearly manifested.

These churches there by marked the boundary between two great periods in the

development of Bulgarian architecture.

In

the treatment of the inner space the churches with a nave and two aisles differed

totally from the single-nave churches. The nave of the former is not simply

a triple repetition of the single nave of the letter. It offers a qualitatively

new spatial, compositional and plastic problem. It is precisely in the nave

that the features of the new architectural system are the most clearly manifested.

These churches there by marked the boundary between two great periods in the

development of Bulgarian architecture.

This boundary is also clearly discernible in the arts included in the interior. The mural decoration which up to the end of the 17th century, was basic element of synthesis in ecclesiastical architecture, now began to nave place to carving and architectural details in relief. The murals no longer covered all the planes of the walls. They were painted only in definite places: wall niches, at the sides of’ windows, etc., most often being replaced by decorative motifs. The ceilings had gold stars painted on a dark blue or indigo background. The carved iconostases, which were compositional parts of the space of the nave, linked with their prepositions, with the principles according to which they were composed and with the entire decorative system, played the principal part in the inner space. This approach to the barrier of’ the iconostasis was created in the 18th century churches of this type and became obligatory for all churches built up to the end of the National Revival period.

The period up to the end of the 18th century was a time in which some of the most perfect carved iconostases were created.

Mount Athos was at that time the centre of the school of art of miniature carving. The carvers who created the small iconostasis of Rozhen Monastery two iconostasis in the Church of the Holy Virgin in Sozopol, the central part of the iconostasis in the Metropolitan Church of Samokov were all trained there. Their pupils later founded the local schools of National Revival woodcarving. The large 13th century iconostases are distinguished by the abundance of ornaments and figural images entwined in then. The human and animal figures depicted in them are close to the fantastic treatment of mythological images. They bear the primitive and irrepressible power of tie primitivism created by popular imagination. The imagination which gave life to them was much closer to paganism than to the Christian principle.

From

the end of the 13th to the ‘50s of the 19th century the nave- and-two-aisles

type of church remained the loading one in the building of churches. However,

the individual components of the spatial composition developed in the first

three decades of this stage. The nave gradually reached its final form of a

rectangular hail, divided into three by two rows of six columns each. It was

roofed with a wooden ceiling, or semi-barrel vaults built of bricks. The three

divisions were of a different height, but all three ‘Mere covered by a saddle

roof, owing to which they were called pseudo-basilicas. A deep balcony-gallery

cut into the nave, played the part of the women’s section of the church. The

stairs leading to it were situated in the nave or the narthex. They were very

rarely built into independent premises. The altar part also developed independently.

Initially it was only a small apse, barely marked in the thickness of the wall.

Later two side niches were added to the apse in order to reach the fully developed

apsidal part of the large Revival basilica-like churches with a nave and two

aisles, drawn into the modeled form of the intricately broken eastern wall of

the church and the richly ornaments cornice above then. On the west a narthex

was added, sometimes open, and sometimes closed (exonarthex). Here, too, the

variant solutions were numerous and surprising in the richness of forms used.

It is through them that the varied spatial solutions of the church buildings

were arrived at, whose exterior architecture was chiefly built up from simplified

spatial bodies.

From

the end of the 13th to the ‘50s of the 19th century the nave- and-two-aisles

type of church remained the loading one in the building of churches. However,

the individual components of the spatial composition developed in the first

three decades of this stage. The nave gradually reached its final form of a

rectangular hail, divided into three by two rows of six columns each. It was

roofed with a wooden ceiling, or semi-barrel vaults built of bricks. The three

divisions were of a different height, but all three ‘Mere covered by a saddle

roof, owing to which they were called pseudo-basilicas. A deep balcony-gallery

cut into the nave, played the part of the women’s section of the church. The

stairs leading to it were situated in the nave or the narthex. They were very

rarely built into independent premises. The altar part also developed independently.

Initially it was only a small apse, barely marked in the thickness of the wall.

Later two side niches were added to the apse in order to reach the fully developed

apsidal part of the large Revival basilica-like churches with a nave and two

aisles, drawn into the modeled form of the intricately broken eastern wall of

the church and the richly ornaments cornice above then. On the west a narthex

was added, sometimes open, and sometimes closed (exonarthex). Here, too, the

variant solutions were numerous and surprising in the richness of forms used.

It is through them that the varied spatial solutions of the church buildings

were arrived at, whose exterior architecture was chiefly built up from simplified

spatial bodies.

The exterior architecture was also enriched. Submitting to the compositional principles of the interior space it produced exquisited examples in which the laconic nature of the spatial solution was most skillfully combined with architectural and plastic forms to created examples of organic and expressive architecture of the type of the Church of SS Peter and Paul in Sopot and the Dormition of the virgin in Elena.

In

the ‘30s the 19th. century the development of the nave-an two-aisles type of

church without a dome reached its zenith. The most perfect examples of this

architectural and compositional type were created, among which are the Church

of St. Nedelya (Dominica) in Plovdiv (1831), the Church of St. Demetrius in

Plovdiv (1831). St. Peter and Pavel in Kotel (1836), the wonderful ‘New Church’

of the Holy Trinity in Bansko (1835), of the Dormition of the Virgin in Elena

(1837) of the Holy Virgin in Pazardjik (1837), and the Church of St. Peter and

Paul in the Convent of Sopot.

In

the ‘30s the 19th. century the development of the nave-an two-aisles type of

church without a dome reached its zenith. The most perfect examples of this

architectural and compositional type were created, among which are the Church

of St. Nedelya (Dominica) in Plovdiv (1831), the Church of St. Demetrius in

Plovdiv (1831). St. Peter and Pavel in Kotel (1836), the wonderful ‘New Church’

of the Holy Trinity in Bansko (1835), of the Dormition of the Virgin in Elena

(1837) of the Holy Virgin in Pazardjik (1837), and the Church of St. Peter and

Paul in the Convent of Sopot.

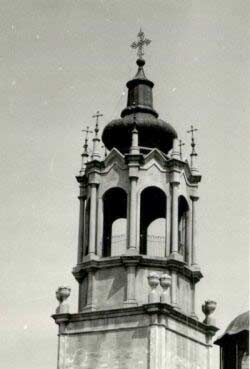

This classical period covers almost two decades. Like all periods of supreme achievements it also marks the limit which the development of a given architectural type could reach. In it the type obtained a finished form and tnereby proved that any further development was impossible. Every repetition was less perfect than the models, and the necessity of new creative searches became obvious. It was at this moment that the revolutionary character of the Nation Revival architecture was manifested.. The period of stagnation was very brief. New trends in the development were marked as early as the 50s, a new element was found which not only imposed itself, but also transformed the pseudo-basilica This element was the dome.

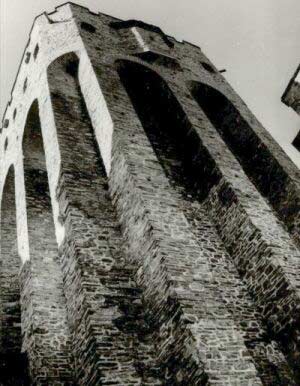

The changes which set in the internal political situation of the Empire after the Crimean War and the recognition of equal rights among the religions, no matter how formal it may have remained gave the Bulgarians possibility of building their churches with belfries and domes Guided by the desire to manifest their national feeling they began to crown their church buildings with domes on a mass scale. It may be said with a fair degree of accuracy that all the churches built after 1860, the year the war came to an end, had domes. Domes were also added on to many of the already existing churches. There were several reasons for which the domed church became firmly established as the basic type: the tradition of Eastern Christian church architecture, whose compositional and symbolical centre was the dome, was followed, and the wish to have the high dome of the Bulgarian churches rival the minarets of the mosques in the towns and villages of the Bulgarian lands was satisfied. The sense of national dignity, supported by the self-confidence of economic success made the Bulgarians of the Revival period strive to rival the predominance of the Moslem temples, erecting high and richly decorated Christian Churches. The basis of this desire for monumental buildings was not religions, It was political: in this period the church was above all, a reflection of social trends.

The

domed church very exactly manifested one of the special forms of carrying on

the tradition. Since the types of domed church characteristic of the Middle

Ages had long since disappeared, there could be no talk of direct continuity.

The process was far more intricate. It took place in two ‘variants. The first

of them was that the domed churches of tile National Revival appeared in regions

where mediaeval traditions of done building had been preserved until late. When

the Ottoman Turks invaded the central regions of the Penin sula their cultural

expansion destroyed the architecture traditions of these regions; in the Western

parts of the Bulgarian lands, however and ill regions distant from the central

routes these traditions manage to be preserved for a considerably longer time.

There the type of domed church was preserved almost to the 17th century.

In the 19th century, by way of the migration groups of builders.

It was transported to the central regions of the Bulgarian lands. This type

of domed churches with a nave and two aisles nave two or three small domes over

the nave.

The

domed church very exactly manifested one of the special forms of carrying on

the tradition. Since the types of domed church characteristic of the Middle

Ages had long since disappeared, there could be no talk of direct continuity.

The process was far more intricate. It took place in two ‘variants. The first

of them was that the domed churches of tile National Revival appeared in regions

where mediaeval traditions of done building had been preserved until late. When

the Ottoman Turks invaded the central regions of the Penin sula their cultural

expansion destroyed the architecture traditions of these regions; in the Western

parts of the Bulgarian lands, however and ill regions distant from the central

routes these traditions manage to be preserved for a considerably longer time.

There the type of domed church was preserved almost to the 17th century.

In the 19th century, by way of the migration groups of builders.

It was transported to the central regions of the Bulgarian lands. This type

of domed churches with a nave and two aisles nave two or three small domes over

the nave.

The second way in which the type of domed church was brought back to life was when it had been preserved in a latent form as a blind dome hidden under the saddle roof of church. The characteristic examples of this feature are the churches in the village of Arbanssi. The region around Turnovo, the old Bulgarian capital in which monasteries and church centres of the Bulgarian Middle Ages have been preserved, has kept important building traditions, one of which is that of the domed church. In the Church of the Holy Archangels in the village of Arbanassi the dome exists as a blind dome. This form is also met with in other churches in this region.

The dome was thus preserved, although it was impossible for it to be snown on the outside of the churches, to be reborn as a form when this was justified by the changed external conditions.

Having

initially appeared as an accidental addiction to the church with a nave and

two aisles, the dome developed in a short time, not only growing in size and

height, but also changing the compositional essence of the church. It became

the organizing centre of the nave, shortening it and raising it in height in

order to crown it as the dominating perpendicular. This process of mutual influence

and change between have and dome passed through several stages.

Having

initially appeared as an accidental addiction to the church with a nave and

two aisles, the dome developed in a short time, not only growing in size and

height, but also changing the compositional essence of the church. It became

the organizing centre of the nave, shortening it and raising it in height in

order to crown it as the dominating perpendicular. This process of mutual influence

and change between have and dome passed through several stages.

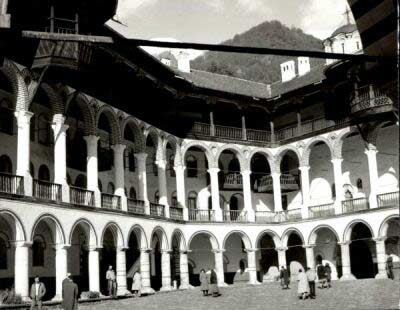

At first the dome was only an element added to the space of the nave in which it was not compositionally included. Resting on six columns in the nave the dome did not violate the inner rhythm of the colonnade, and did not change the dimensions and proportions of the space. It was timidly manifested in the exterior volume of the church without changing the rules of composition, according to which the exterior architecture of the basilica-type of church with a nave and two aisles was built. Gradually, however, the builders increased the dimensions of the dome and began to look for its place in the general compositional plan. Moreover, they returned to the old plans of the domed cruciform church, placing the columns on which the dome rested in such a way that they resembled an inscribed cross. Examples of this kind are to be found in the churches of the Balkan Range, such as those of the Holy Virgin in Gabrovo and of the Nativition of the Virgin in Elena.

Nikola Fichev, the great builder of the National Revival period, developed the type of the domed church in another direction. He connected the dome with the section through the basilica’s nave, considering that it was this solution which was the most suitable for our service. He skilfully removed all superfluous elements from the inner space, obtaining extensive interior volumes merging into soft forms, logically crowned by the perpendicular of the central dome. In the outer architecture of the churches Nikola Fichev used the richest elements of the National Revival architecture without restricting himself to the framework of ecclesiastical construction alone.

Combining

tradition and innovating conceptions, the builders of the National Revival period

created a qualitatively new type of the domed church of the Revival period.

They also wove into it outside influences, which are the most strongly manifested

in the composition of the interior space. The harmonious balance of the composition

is a basic principle in the spatial solution of the pseudo-basilica type of

the nave-and-two-aisles church. This Renaissance principle was implemented by

co-ordinating the elements, and was later replaced by the Baroque principle

of co-subjection. Having passed along the complex ways along which the influences

of European architecture were transmitted, it imparted the sense of Baroque

space which distinguishes our ecclesiastical architecture in the second half

of the 19th century. The principle of co-subjection is most fully manifested

in the domed churches a where the dome unites all the elements of interior space,

subjecting them by its predominant volume. The dome introduces tenseness into

the interior space, also expressed by the rhythm given to the elements: columns,

wall planes, and even spatial units.

Combining

tradition and innovating conceptions, the builders of the National Revival period

created a qualitatively new type of the domed church of the Revival period.

They also wove into it outside influences, which are the most strongly manifested

in the composition of the interior space. The harmonious balance of the composition

is a basic principle in the spatial solution of the pseudo-basilica type of

the nave-and-two-aisles church. This Renaissance principle was implemented by

co-ordinating the elements, and was later replaced by the Baroque principle

of co-subjection. Having passed along the complex ways along which the influences

of European architecture were transmitted, it imparted the sense of Baroque

space which distinguishes our ecclesiastical architecture in the second half

of the 19th century. The principle of co-subjection is most fully manifested

in the domed churches a where the dome unites all the elements of interior space,

subjecting them by its predominant volume. The dome introduces tenseness into

the interior space, also expressed by the rhythm given to the elements: columns,

wall planes, and even spatial units.

Parallel with the domed churches, saddle-roofed basilicas with a nave and two aisles continued to be built during the second half of the 19th century. Their plan and spatial composition preserved its traditional forms but certain changes also set in. Under the influence of the domed churches the form of the covering of their interior and exterior volume changed. Under the same influence the single-nave churches of the second half of the century developed. They became markedly perpendicular in volume.

That distinguishes the development of the basic types of church buildings in the last decades of the Bulgarian National Revival period, is the trend towards new architectural and compositional forms and a clearly marked monumental quality.

The ecclesiastical art of the National Revival period in these decades was going through its last period. It developed almost entirely under the influence of the newly-created secular art. The mural decoration of that time was mainly decorative in character and the figural scenes were often placed In frames resembling easel pictures.

Carving

had already bad its ‘Golden Age’. The large iconostases were cabinet work and

only in the monasteries and in certain small village churches could carved iconostases,

the works of the old schools, be found. Architectural and plastic details became

the principal decoration of the churches. The church walls were most often left

white, with the capitals of columns, decorative lattices and parapets, and chairs

ornamented with carving standing out against them, the effects of a varied lighting

being sought after. The secular principle captured church architecture and the

new aesthetic criteria of the period, criteria which were to be manifested in

full force in the public architecture of the post-Liberation period were built

up within its framework.

Carving

had already bad its ‘Golden Age’. The large iconostases were cabinet work and

only in the monasteries and in certain small village churches could carved iconostases,

the works of the old schools, be found. Architectural and plastic details became

the principal decoration of the churches. The church walls were most often left

white, with the capitals of columns, decorative lattices and parapets, and chairs

ornamented with carving standing out against them, the effects of a varied lighting

being sought after. The secular principle captured church architecture and the

new aesthetic criteria of the period, criteria which were to be manifested in

full force in the public architecture of the post-Liberation period were built

up within its framework.

Having appeared extremely late in comparison with the remaining European countries, the Bulgarian Renaissance in art and architecture bore its specific features conditioned by historical circumstances. They were manifested in the entire development of the ecclesiastical architecture of the National Revival period. In this architecture mediaeval and folk principles, ancient eastern forms and the forms of Western architecture most freely adopted and Interpreted, the new conception of architectural composition and the old compositional methods, were all welded together. Despite its eclectic character, this architecture remained monumental and expressive, bearing the spirit and atmosphere of the revolutionary epoch which gave it birth.

© Маргарита Коева

=============================

© Електронно издателство LiterNet, 01.04.2004

Маргарита Коева. Архитектурното наследство и съвременният свят. Сборник студии

и статии. Варна: LiterNet, 2003-2012