Издателство |

| :. Издателство

LiterNet |

Медии |

| :. Електронно списание LiterNet |

| :. Електронно списание БЕЛ |

| :. Културни

новини |

Каталози |

| :. По

дати : Март |

| :. Електронни книги |

| :. Раздели / Рубрики |

| :. Автори |

| :. Критика за авторите |

Книжарници |

| :. Книжен

пазар |

| :. Книгосвят: сравни цени |

Ресурси |

| :. Каталог за култура |

| :. Артзона |

| :. Писмена реч |

За

нас |

| :. Всичко за LiterNet |

ARCHITEKTON ALEXI RILETS

Klara Daskalova-Obretenova, Aleksander Obretenov

Master, away you are now,

A stone you are, shining light…

Dragomir Shopov

Architekton Alexi Rilets.

Sculptor: Prof. Sekul Krumov, Artist: Klara Daskalova-Obretenova.

Photographer: A. Obretenov

Alexi Rilets was born in 1760 near the town of Debar, at the Lake of Ohrid, and he died in 1850 in the town of Rila (a then village); he lived to be 90. He received his first lessons at the famous Debar School of Building and Woodcarving.

He arrived in the village of Rila as a builder, when he was 20, in order to take part in the construction of the Rila Monastery and the buildings around it. There he met and married Maria of Yagoridko’s clan. By January 2004, the descendants of their family amounted to already 511.

Prof. Mihail Enev (1997) announced, “Master Alexi Rilets…worked in villages near Melnik and at many places in Macedonia. In his native vicinity of Debar he learnt his craft and worked as a woodcarver. A number of historians report that he worked as a builder also in some Mount Athos monasteries. He built churches in Razlog and in the village of Bistritsa, near Doupnitsa, and he made the fretwork bishop throne in St. Archangel Michael Church, in the village of Rila. Some old-time houses in Rila are also considered works of his.” The cloister /cell/ school of his son, Dimiter the Teacher, which has been declared historic monument, and his family house, declared monument of culture, are among these.

His only undeniable product here is the bishop throne. It was in the old St. Archangel Michael Church, at the graveyard. After a severe earthquake, the throne was taken to the new St. Nicolas Church. A big inscription on its backrest reads, ‘Donor and dedicator in year 1819 Chief Master Alexi Rilets for eternal memory.’ This means that Master Alexi made and bestowed it for eternal memory.

A bishop throne that Master Alexi made in 1819. It is in

St. Nicolas Church, in the town of Rila.

Photographer: T. Nenkova

The Rila Monastery, with its history of over a millennium, was established at the time of St. Ivan Rilski. Hieromonk Neofit Rilski (1879) considered like this the issue of whether as early as the time when St. Ivan Rilski lived in the cave (930-936) a monks’ dwelling was built at the place of the present monastery, “Now another question arises here, ‘Was the present monastery that is about one hour walk from the place where the Reverent Father lived, passed away, and was buried built as early as when he was alive, or it was built soon after his decease, or long time after that?’ His life story says nothing about it, but it is known by word of mouth why when he was alive, at that place, where the monastery now is, a dwelling was built for monks (which has also been confirmed by the very Testament of the Reverent Father), and for what reason.”

Robbed and devastated many times, the Rila Monastery has survived until now in order to conserve and show to the world the Bulgarian way of living and culture, as well as the power of the Bulgarian spirit, and this is why it has not been called accidentally ‘the soul of the nation.’

At the time when Master Alexi was in the summer of his strength, in 1784, the Rila Monastery restoration was completed, after the plunders of 1765, 1768 and 1778. When we follow the time and the possible separation of a young family (Alexi Rilets and Maria Yagoridkova), when their son, Dimiter, was between 1 and 13 years old, it is most likely that the father was then near his family, i.e. he has participated in the construction of the Rila Monastery in 1784, in the expansion of Hrelyo’s church in 1784-1792, and in the building of St. Luke Church, in the east of the Rila Monastery, in 1796. His participation in the construction of the monastery wings in 1784 was the main reason for inviting him again, 32 years later (for the period 1816-1819) to build up the monastery wings, this time not as an ordinary mason but as the chief master who had gained rich experience with such construction.

A metal plaque on the western gate with the superscription:

‘the year 1784’.

Photographer: A. Obretenov

According to us, when we have a look at the time of building the particular parts of the Mount Athos monasteries, as the archeologist Sotiris Kadas (2001) has described it in his guidebook entitled ‘Mount Athos,’ i.e. the time between 1783 and 1815 when Master Alexi was between 23 and 56 years old, we see that he is likely to have participated in the construction of the following monastery structures:

1. Hilendar /Chelandar/ is one of the five oldest monasteries in Mount Athos. A devastating fire destroyed it in 1722. Bulgarian masters took part in its renewal. In the north of its church, almost in the middle of the yard, there is a holy mineral water spring covered with a protective dome on eight vaulted columns, all built in 1784. The vaulted column structure resembles very much that in the Rila Monastery.

2. The large St. George Cathedral in Zographou Monastery was built in 1801 in the place of an older church, with funds of the priors Evtimiy and Porfiriy. St. George Cathedral is one of the largest in Mount Athos; it is 36.60 m long and 16.80 m wide. “The temple is a typical example of the cult church buildings of the 17th and 18th centuries, which were built in other Balkan countries as well. This church has not accidentally been used as the prototype of the main church in the Rila Monastery (Enev 1984).”

3. The old clock tower of Zographou Monastery, which was built in 1810, in the middle of its eastern wing; it was additionally built in 1860-1869.

4. The monastery wings with their monastic cells, which were built in the northwestern part of Zographou Monastery in the period 1787-1869, during the abbacy of Antim Rizzov of the village of Kalkovo, near Stroumitsa. The northwestern part of the monastery, which was built at that same time and, additionally, in 1860-1869.

5. The Holy Mother of God Priory, at Xilourgou Monastery, has three churches ‘Assumption,’ ‘St. St. Kiril and Metodi,’ and ‘St. Ivan Rilski.’ The last one was completed in 1820. This church is supposed to have been built with donations from ‘a Rilan archimandrit,’ Prior Sofroniy. Its frescos are typical of the Bansko School of Arts. The priory is among the oldest in Mount Athos. It is in the northwestern part of the peninsula. According to old sources of information, the Byzantine Emperor Alexis I Comnenus bequeathed this place to the Russians, in 1080. After the Russian monks left it in 1169, it was given to the Bulgarian monks.

The construction of monasteries usually began with the defensive stonewalls around the dwelling, then a church would be built, after it - the cathedral (the main monastery church), and finally - the monastery wings with the monk cells, and the dome over the holy spring. It was probably the excellent work of Master Alexi at some of these building sites that brought him the title ‘architekton’ before he was invited to build the Rila Monastery, as at the beginning of the construction of the Rila Monastery in its present aspect, on 1 May 1816, on the first memorial slab, above the front door of the mill in the northern end of the eastern wing, he was recorded as ‘Alexi Architekton.’

Arch. Dr. N. Touleshkov (2002) expressed the following opinion, “It seems that at that time he (Master Alexi) designed and built structures of importance for the State, for which a diploma of a practitioner architect was conferred on him as he was recorded on the memorial slab of 1816, built-in in the northeastern residential wing of the Rila Monastery, as ‘ALEXI ARCHITEKTON.’”

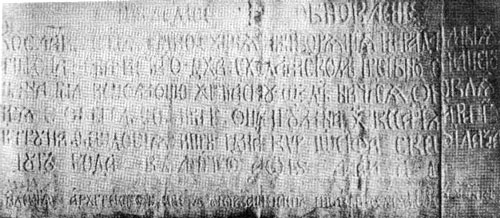

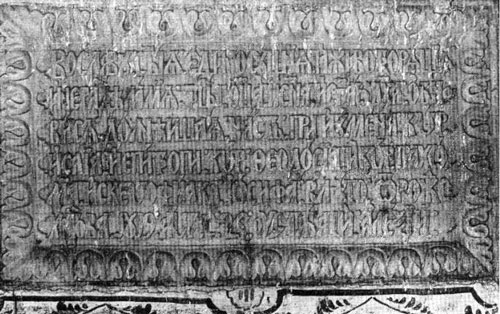

The superscription on the first slab, above the front door of the mill, at the north end of the eastern wing reads:

“The last renovation

For the glory of the Consubstantial, Life-giving, and Inseparable Trinity of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, with the interceding of our Reverent Father Yoan Rilski, and with aid from Christians, this Holy Dwelling here began to renovate with Father Abbot Hadji Kessariy, Churchwarden Teodossi, and the Reverent Elder Yossif, in 1816. In the year of our Lord 1816, on the first day of May. Alexi architekton, that is chief master builder. And he who wrote that is an alumnus of this same Yossif.”

The first memorial slab above the front door of the mill

at the northern end of the eastern wing.

Photographer: Prof. Arch. G. Stoykov

Building-up the Rila Monastery in its present aspect began in 1816 from its northeastern return, and it continued for 30 whole years.

Senior Research Associate Arch. Yordan Tangarov (1996) wrote, “This incredible construction united the thoughts and reveries of the ecclesiastical figures of Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia; it gathered considerable donations from hundreds of Bulgarian towns and villages; it united the builders’ guilds of all Bulgaria. Hundreds of building teams, groups of professional builders, masons, stoneworkers and woodworkers were attracted by the patriotic call to turn the people’s reverie into a national monastery unique and incredible that has been intended in its capacity of advance guard of the nation to compete with the most glorious Mount Athos.”

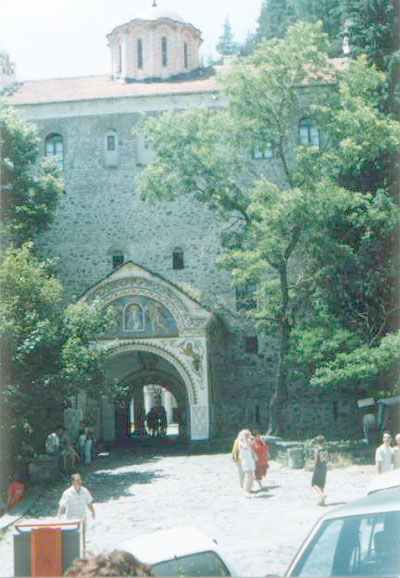

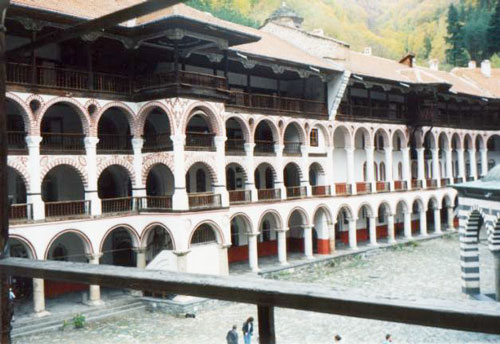

The external façade of the eastern wing of the Rila

Monastery (1816), with the Samokov gate.

Photographer: A. Obretenov

View of the Rila Monastery courtyard and the surrounding

peaks from the Doupnitsa gate (1819). Parts can be seen of the northern (1817)

and eastern (1816) wings of the monastery, Hrelyo’s tower (1335), and

the church (1837).

Photographer: A. Obretenov

Architekton Alexi Rilets planned to build-in in the middle of the eastern wing a high clock tower with a belfry, which was to rise above Hrelyo’s one and remind to all mortals that they were in the power of time. Such clock towers had been built-in in the middle of the eastern wing of each of the largest Mount Athos monasteries. This must have been the reason for building this wing to only 1/3 of its length in 1816.

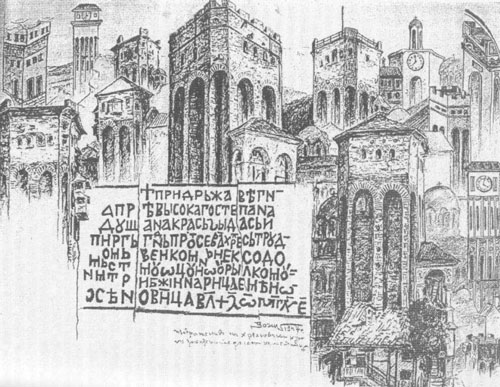

Rizov’s graphical drawing confirms this with its large number of depictions of Hrelyo’s tower from the moment of its erection to 1947. The drawing has been made on the bases of old monastery gravures. If we carefully look at Hrelyo’s tower of the time before the battlements on its roof were built, when there was a parapet only, we shall see on the right behind it part of the eastern monastery wing, with its cells, attached to a high clock tower with a belfry, and, below the clock, pilasters finishing with a vaulted arch in the tower, in resemblance with the pilasters and arches that can be seen on Hrelyo’s tower on the right of which and a little bit forward the dome of the monastery church can be seen. Such must have most probably been Master Alexi’s ideas of the future appearance of the monastery, when he started its construction. In this way he marked even the place where the clock tower should be. This only gravure that shows a nonexistent clock tower, must have been a personal drawing of Architekton Alexi, as all the other ones reveal details that were really built and reconstructed in the course of time.

For example, the clock in the upper left and lower right corners of the drawing is mounted on Hrelyo’s tower such as it is depicted on the gravure of the Rila Monastery in its initial aspect of the 17th century. This clock tower that Hrelyo built considerably differs in its shape and structure from the clock tower that is supposed to have been drawn by Architekton Alexi Rilets. All the rest of the roof structures on Hrelyo’s tower had already been built - the four corner columns, the tilted roof, the parapet, and the battlements.

The acute angle between the eastern and northern wings of the monastery, which Architekton Alexi built, and the considerable cutting-in of the eastern wing into the monastery yard in the direction towards Hrelyo’s tower have been determined by the relief of the ground and by the bend of Drushlyavitsa River. The architekton envisaged to build by means of this clock tower a natural return in the middle of the eastern wing, so that, on the one hand, the clock would approach Hrelyo’s tower in order to become more easily noticeable by visitors to the monastery and, on the other, the southern part of the eastern wing would reach the eastern corner of the southern wing that Master Milenko would built.

The modern architects who completed the eastern wing of the monastery in 1961 should have taken into consideration the vision of Architekton Alexi Rilets, and they should have kept the general architectural ensemble such as Master Milenko kept it when he built the southern wing in 1847.

Hrelyo’s towers that Rizov drew (1947) with the designed

clock tower.

Photographer: Prof. M. Enev

Part of the Rila Monastery - the north wing (1817) with a

staircase, the kiosk that Krustyu the Debaran built (1834), and a firewall (1834).

The great architectural order with and without intermediate arches of the columns

can be seen, as well as the cookhouse entrance and dome.

Photographer: A. Obretenov

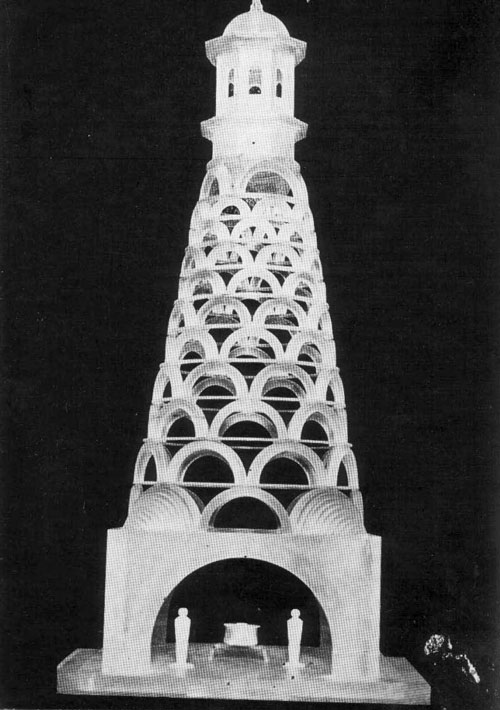

The cookhouse Master Alexi has built in the Rila Monastery is of the central type, with arches. It has entirely been built-in in the northern wing, between monk cells. Its exterior walls are inaccessible to visitors. Its height is impressive - 24 m. It begins with a huge space for the fireplace, with four vaults, and it grows up as a pyramid. Its walls are formed by 10 rows, each composed of 8 arches, pendentives, and trumpet arches, all in a chequer arrangement. In the direction towards the roof, they gradually diminish in size, in contrast to those in Vekereshti Monastery that are of saltatory diminution. In the last row, four large arches have been placed instead of 8 small ones, in order to bear the huge weight of the top portion of the cookhouse (Hristov 1957) - another confirmation of its builder’s wisdom.

The cookhouse finishes with a beautiful lantern and a small dome with a cross - its only part that can be seen above the roof. Little light comes in through its openings.

“The arch system dominates almost completely in the cookhouse structure. It provides the triple architectural unity of the interior and exterior façades and Hrelyo’s tower. And again the influence of nature upon Master Alexi’s imagination can be felt. The chequer arrangement of the arches suggests the mirror image of a multilayer spruce cone …

We can hardly imagine today the enormous effect, which the Rila Monastery architecture and cookhouse had on the consciousness of the then Bulgarian. He would leave the monastery cheered and in high spirits, and with increased self-confidence that he, too, had together with the other nations the right to live freely, to have a better life, and to struggle for it. And here is the great artistic, patriotic, and educative effect of monuments of culture that are as important as the Rila Monastery and its cookhouse.” (Stoykov 1976).

At EXPO 1970 in Tokyo, Japan, the Rila Monastery cookhouse was lastingly reproduced as a unique architectural achievement.

Model of the cookhouse.

Photographer: Prof. Arch. G. Stoykov

On the second slab, placed at a noticeable site, above the Samokov gate of the eastern wing, so that many guests could see it, it is written beautifully among suitable fine ornaments and with a lot of love:

“This church and patriarch dwelling was by the Father built, by the Son established, and by the Holy Spirit renovated under the protection of our Holiest Lady, the Mother of God, and with the interceding of our Holy and Reverent Father Yoan, and with pieces of advice, work, and donations from the whole brethren, and charities from Christians, was built-up from its bases during the abbacy of the Most Honest Gentleman Abbot Yoassaf and with the support (in the care) of the Most Honest Prior and Churchwarden Teodossi and the Reverent Elder Yossif, in the year 7325 of the creation of the world, or the year of our Lord 1817. Chief Master Alexi of the village of Rila, 1817.”

The second memorial slab above the Samokov gate of the eastern

wing.

Photographer: P. Kalchev, after Prof. H. Hristov

The Rila Monastery - the exterior façade of the western

wing (1819) with the Doupnitsa gate.

Photographer: A. Obretenov

Part of the Rila Monastery - the western wing (1819) with

the Doupnitsa gate, a firewall, and two wooden kiosks.

Photographer: A. Obretenov

On the third slab, placed at a noticeable site, above the Doupnitsa gate of the western wing, also beautifully inscribed and decorated with nice plastic stonework, it is written:

“For the glory of the Holy, Consubstantial, Life-giving, and Inseparable Trinity of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit the lowest part was renovated with Abbot Issai, the churchwardens Teodossi and Pahomiy, and the Reverent Elder Yossif in the year of our Lord 1819, on 25 August. Chief Master Alexi”.

The third memorial slab above the Doupnitsa gate of the western

wing.

Photographer: Prof. Arch. G. Stoykov

In spite of the envy, the glory of the Rila Monastery was spread over the world. Hieromonk Agapiy wrote, “The monastery was prosperous, and during their time it became famous for taught monks and a wonderful building, thus obtaining certain worldly glory and honour (Sprostranov 1901: 15, 20).”

A great disaster befell the whole Bulgarian nation on 13 January 1833 when a great fire broke out in the Rila Monastery. Huge flames spanned it and they destroyed everything that could burn. The whole wooden part of the monastery was destroyed. What remained to stick out was only fumigated silent stonewalls and columns cracked from the high temperature. Unfortunately, a large proportion of the monastery archive burnt out, too, and this makes it difficult to study the deed of Master Alexi.

Traces on the outer wall after the great fire of 1833; one

can see the places (holes) of the floor beams of a cell, the fireplace, and

the window, now walled-up. Under the cell there was a low cellar with a niche

and a loophole for firing.

Photographer: Prof. Arch. G. Stoykov

The news about the fire deeply excited Master Alexi’s restless spirit. He could not help meeting the new challenge also because the evildoer had already left this world. Being then 73 years old, he did not get frightened, and he even passed through the gate of the Holy Dwelling with greater ardency and enthusiasm.

Of course, in the latter 14 years Master Alexi had been gaining greater, new experience. Having taken into consideration the increased requirements as well, he took brave and decisive steps to making the monastery even much grander, finer, more captivating, attractive, and fire-resistant.

With the efforts of a very large number of volunteer builders, workers, and masters, over 3,000 men who had come there with their families, the monastery was completed within a time short enough to be a record in building - about 10 months only. Then, as it was with the renewal of the monastery, Master Alexi would receive aid from the clergy, mainly Yossif, this time in his capacity of the abbot, and Churchwarden Teodossi. An enormous amount of organizational work was done. The necessary funds were looked for, large amounts of materials were provided, and the best master bricklayers, woodcarvers, and iconographers were found…

In order to protect the monastery against future devastating fires, the master raised firewalls from its foundations up to above its roof. They obstruct the loggias as well, as the passage from one loggia to another is through a stable iron door. Each firewall has an architectural aspect of its own. Such firewalls “do not occur in other buildings (Hristov et al. 1957: 28-30, 33).”

Picturesque, new, wooden kiosks of one or two stories, differing in splendour, appeared on the interior monastery façade. Ktustyu the Debaran made one of these kiosks. He justified Master Alexi’s confidence as he applied all his skill and diligence in its elaboration. The ceiling, decorated with fretwork, is especially distinguished for its skillful make. On one of its friezes, deservedly stands the superscription, ‘In the year 1834, in April, Master Krustyu the Debaran of the village of Lazaropolé, made a kiosk with his work and devotion, in order to save his soul.’ It is clear from the superscription that Master Krustyu the Debaran has bestowed the kiosk on the Rila Monastery (Stoykov 1976).

Prof. Arch. G. Stoykov (1976) discussed this issue in detail, and he proved the leading role of Architekton Alexi Rilets in the restoration of the Rila Monastery after the fire in 1833, “The three superscriptions, on the northern, eastern, and western wings, in which it is stated that Master Alexi built these wings (1816-1819) have been preserved after the fire. Their availability excludes the participation of other masters in the restoration of the incinerated wings. Because it cannot be assumed that, if other masters had participated in the restoration of the wings, to which some improvements (firewalls, kiosks, etc.) have been made, they wouldn’t have marked at the respective places, as the custom at that time was, their work by their names, dates, and places to be found at… The three superscriptions about Master Alexi reveal his participation in one and the same work - the renewal of the monastery before and after the fire, besides, in the same aspect with small exterior additions and interior changes. Therefore, we have the full reason to consider that it was Master Alexi who restored the three wings, as he knew their structure and architecture well.”

According to a ready-to-publish study by Sen. Res. Assoc. Arch. Y. Tangarov, it is evident that the cell and the cellar under it, which Prof. Arch. G. Stoykov and students have documented, were not on the second and third floors but on the third and fourth ones, above the cookhouse. If the cookhouse dome was on the second floor only, and a narrow chimney continued upwards, there would have been a cell built-up on the third floor as well, instead of a cellar, and the cellar would have been on the second floor. This means that the northern wing was of 4 floors even before the fire of 1833, and the cookhouse was built in 1817-1818. The cell was not restored after the fire, because the newly formed Teteven room (a room built and decorated in the style of the town of Teteven - translator’s note) had blocked the direct access to it. The additional walling-up of the cookhouse body, in its upper portion, from outside, has probably been necessitated by cracks from the high temperature of the fire, like those on the outer support marble columns on the ground floor, as these columns had to be additionally tied with metal rings.

Dr. Arch. N. Touleshkov (2002) wrote, “In fact, this (the Rila Monastery) is his (Architekton Alexi Rilets’s) most famous work built up between 1816 and 1819 and reconstructed again by him after the fire in 1833. This is also one of the most perfect buildings of the Bulgarian Renaissance, as in its tectonics, so in its architectural aspect. The great architectural order that was unique for the Balkan Peninsula at that time, the magnificent cookhouse body modeled in such a complex way, and the wonderfully formed rooms and monk cells created after the restoration work that succeeded the fire, have no analogues even in Mount Athos.”

In the Arch. & Art Newspaper of 7 April 1998, Arch. Tangarov shared with admiration, “It is difficult to analyze the organization which Protomaster Alexi created with the participation of tens of teams from Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia. The keeping of the deadline of the enormous construction, without any hints at contradiction between the numerous masters and the architekton, is more than indicative. First of all, the Bulgarian masters would be learning about and from one another in the process of work. This was more than a school; it was an academy. Probably, most of the masters who have built our Renaissance architecture have passed through it.”

Sen. Res. Assoc. Arch. Y. Tangarov determined the Rila Monastery as the most significant monument of architecture of all times in the history of Bulgaria.

Being up to his eyes with restoration work, or for some other reasons, Master Alexi Rilets again failed in realizing the plan he had made for the entire building-up of the Rila Monastery. This is why other good masters were also invited - Pavel of the village of Krimin, near Kostur, to build Sveta Bogoroditsa Church (The Holy Mother of God Church - translator’s note) (1 May 1834 - 26 October 1837), and Milenko of Blateshnitsa, near Radomir, to raise the southern wing of the monastery (1847) (Stoykov, 1976).

Neofit Rilski (Vassiliev 1965) pointed out that building Sveta Bogoroditsa Church had been assigned to Architekton (Chief Master) Pavel, in accordance with a plan two monks had made preliminarily, as they had visited the Mount Athos monasteries. Master Pavel was given full freedom to demonstrate, by this church, all his skill. He promised to make it more perfect than its prototype. He has been recorded as ‘architekton’ on a marble slab built-in in the cornice of the open gallery in front of the church entrance. He has also been mentioned as such in the documents in the Rila Monastery. He signed a letter of his as ‘protomaster and maimar’ (i.e. the Turkish for architect) (Touleshkov 2002).

The monastery church he built was the largest one on the Balkan Peninsula at that time (Koleva 1989: 4, 21, 38).

Master Milenko built up the highest wing, the southern one, of the Rila Monastery with residential rooms in the image of the previous ones. There is a brick superscription about him below the cornice on the western wall of the wing he has built - “1847 Milenko Chief Master, Radomir”.

In 1961 the Rila Monastery was declared national museum monument.

At EXPO 1970 in Tokyo, Japan, the Rila Monastery cookhouse was lastingly reproduced as a unique architectural achievement.

In 1980 the Rila Monastery won the reward ‘Golden Apple’ of FIJET, the International Federation of Journalists and Writers on Tourism.

In 1983 UNESCO avowed the Rila Monastery a monument of world culture, together with other 6 Bulgarian historic and archeological monuments: the Kazanluck Tomb, the Tomb at the village of Sveshtaré, near Nessebar, the Ivanovski Rock Churches, the Horseman of Madara, and the Church of Boyana. The monastery contributed to the ranking of Bulgaria third in the world in number of sights, after Italy and Greece. “In the 300 monuments that UNESCO avowed, 7 are in your country. This is an enormous wealth,” said the President of the International Council of Monuments of Culture (ICOMOC), Mr Rolan Sylva, in the National Palace of Culture (NPC), in Sofia, on 10 October 1994.

On the territory of Rilski Manastir /Rila Monastery/ Nature Park, among the beautiful Manastirski /Monastery/ Lakes (2 in number), Dyavolski /Devil’s/ Lakes (7), Smradlivi /Stinking/ Lakes (4), Ribni /Fish/ Lakes (2), and Marinkovsko /Marinkov’s/ Lake, that bestow water on Rilska /Rilan/ River, rises the impressive, hardly accessible peak that is the highest one in the park. It is called ‘Rilets Peak’ (2,713 m alt.) in honour of Architekton Alexi Rilets. There are two other peaks near it - in the east - Yossifitsa Peak (2,696 m alt.), named in honour of Elder Yossif and, in the west - Teodossievi Karauli /Teodossi’s Sentries/ Peak (2,671 m alt.), named in honour of Churchwarden Teodossi. The names of Yossif and Teodossi are written together with the name of Architekton Alexi on each of the three memorial slabs on the respective monastery wings. In the south, among the Sinyo /Blue/ Lake, Chernatishki /Chernatitsa/ Lakes, Mramoretsko /Mramorets/ Lake and Chernopolyanski /Black Lawn/ Circus, rises Pavel Peak (2,667 m alt.), named in honour of Master Pavel, the builder of the monastery church.

A memorial slab to Master Alexi Rilets, on Rilets Peak.

Photographer: A. Obretenov

The monument to Architekton Alexi Rilets, near the central

square in the town of Rila.

Photographer: A. Obretenov

Unfortunately, the hard time we live today in forces a number of young and intelligent Bulgarians to leave our country in order to seek fortune abroad. They should know the millennium-old history of our wonderful, small country that has preserved the memory of the hope and faith of the people’s enlighteners who carried in their hearts the Bulgarian spirit. The spirit which, like a guiding star, would not once take them out of the darkness of obscurantism, so that we could survive through the ages and prove to the world that Bulgaria deserves a better fate and that it needs new Renaissance. This requires strong persons, followers of Alexi Rilets the architekton - the patriarch of Bulgarian architects (after Dr. Arch. Touleshkov and Arch. Tangarov).

This obliges us to take the shroud of oblivion off Architekton Alexi Rilets, who laid the beginnings of the Rila Monastery in its monumental present appearance, to find, properly assess, and preserve the architectural wealth he has bequeathed us, and be donors as generous as him.

The white-stone monument to the miracle worker saint, Ivan Rilski, at the turn for the Rila Monastery on the Sofia-Blagoevgrad road, and the bust of Architekton Alexi Rilets, at the square in the town of Rila, clearly outline the way to the Rilan Holy Dwelling. The trinity of the Rila Mountains, the Rila Monastery, and the town of Rila shines like a bright constellation on our native vault of heaven, and Master Alexi flies on and on through the ages.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Enev 1997: Enev, Mihail. The Rila Monastery. Sofia, 1997 (In Bulgarian).

Hristov et al. 1957: Hristov, H., Stoykov, G., Miyatev, K. The Rila Monastery. Sofia, 1957 (In Bulgarian).

Kadas 2001: Kadas, Sotiris. “Der Berg Athos”, Archaeloge. Athen: Ekdotike Athenon S.A., 2001. (In German).

Koleva 1989: Koleva, M. The Rila Monastery, Bulgaria. 1989 (In Russian).

Rilski 1879: Neofit Rilski, Hieromonk. Description of the Bulgarian Holy Monastery Rilan. Sofia: The Quickly Printing Press of Yanko Kovachev, 1879 (In Old Bulgarian).

Sprostranov 1901: Sprostranov, E. Materials on the History of the Rila Monastery. Collection of Folk Works. // Knizhnina i Naouka (Literature and Science) Magazine, 1901, № XVIII (In Bulgarian).

Stoykov 1976: Stoykov, G. Master Alexi and Master Kolyo Ficheto. 1976 (In Bulgarian).

Tangarov 1996: Tangarov, Yordan. Academy of the Bulgarian Plastic-Arts Culture. // The Arch. & Art Newspaper (Sofia), Issue of 1, October 1996 (In Bulgarian).

Tangarov 1998: Tangarov, Yordan. Protomaster Petko Boz. // The Arch. & Art Newspaper (Sofia), Issue of 1, April 1998 (In Bulgarian).

Touleshkov 2002: Touleshkov, Nikolay. In Praise of the Protomasters. // The Arch. & Art Newspaper (Sofia), of 12-19 June 2002 (In Bulgarian).

Vassilev et al. 1973: Vassilev, A., Sillyanova-Novikova, T., Trifonov, N., Lyubenova, I. Plastic Stonework. Sofia: Publishing House of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (BAS), 1973 (In Bulgarian).

P.S.: You can find more information in the book ‘Architekton Alexi Rilets,’ issued in 2005.

© Klara Daskalova-Obretenova, Aleksander Obretenov

© Konstantin Pchelinski, translated

=============================

© E-magazine LiterNet, 19.04.2005, № 4 (65)